SOMETIMES IT is necessary to do things back to front and start with the end of a story. This one finishes in the early autumn frosts of northern Canada, amongst the stunted pines and endless impenetrable wilderness of the sub-Arctic tundra with the howl of the timber wolf providing a haunting sound track to the nightly kaleidoscope of Aurora Borealis.

Just a few hours earlier I had been lying on a strip of sandy shore close to the lake’s edge letting the hot sun ease away cares and woes and contemplating a satisfying lunch of fried lake trout and northern pike fillets, creamed corn and beans washed down with a few beers. The fish, of course, caught by ourselves earlier in the morning.

It was easy to believe the local Indian guide that no human had ever set foot on that small sandy shore before. At our backs was a solid jungle of pine, thorns, brambles and dense vegetation stretching for hundreds upon hundreds of miles. Before us lay several thousand acres of Hatchet Lake, a massive sheet of freshwater that makes up just part of the Fond du Lac river system.

It had been an extraordinary few days at the beginning of September. The mornings were already freezing, our breath crystallising in the chill air as we tackled up and set off across the many miles of the lake. This was BIG fish territory where the lake trout grow to a prodigious 50lbs or more and vie with northern pike for true leviathan status.

The anglers who visit the remote resort, accessible only by small plane, come armed with fishing tackle which seems to owe more to John Brown Engineering than to featherweight Hardy wands. As an ardent fly-fisher weaned on Scottish hill lochs and small rivers, my rods, reels and lures appeared ludicrously puny when faced with the Charles Atlas equipment wielded by north American sportsmen and women.

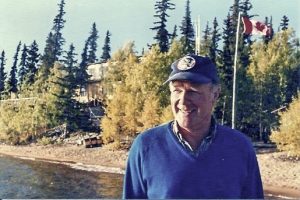

I’d travelled thousands of miles partly for the fishing but also to meet The Man from Hatchet, George Fleming, a Scottish entrepreneur who, with all the ingredients of a Boy’s Own tale, had built the classy fishing retreat more or less single handed in one of the most remote and inhospitable regions of the planet.

It was a wonderful yarn recording privileged early days at a private school in Scotland, forsaking comfortable civilisation for life as a Hudson’s Bay trader and the extraordinary risks taken to drive heavy equipment over frozen lakes to build his dream fishing resort, complete with its own airstrip, on a small island in the middle of the Canadian nowhere.

Most of the guests were fanatical anglers from all over the US tempted by the lure of larger-than-life catches of lake trout, northern pike and grayling, five-star service and a backdrop of untouched wilderness.

The sturdy log cabins set along the shore-side boasted all mod-cons. At six every morning, staff would enter to fire up each wood-burning stove so that when we rose at seven, the cabins were snug and warm. The same procedure was repeated in the evening.

The food of course came in two quantities; large and super-gargantuan feast. The menus were clearly aimed at the American palette, rich sauces, most of the content of the Canadian grain belt and lots of fry-ups, but nonetheless with some skillful pruning and careful ordering, could be tailored to a more marginal carbohydrate diet.

Especially when, as you will shortly see, I got on closer terms with the head of domestic services at the resort.

We think that here in Scotland we have some of the wildest, unspoiled landscapes in Europe on our doorstep. And we do. The combination of mountain, moor, loch, glen and seascape is unique and provides a bounty of some of the wildest, unspoiled fishing you could wish for. It is fabulous and small wonder it attracts thousands of visitors every year.

Canada does wilderness too. But on a scale of about 20 times larger. I flew north from Saskatoon in a small plane for more than three hours and for much of that time the landscape below was an unending panorama of lakes and wilderness forest stretching from horizon to horizon. It was as if the top of the world was still drying out from a millenium-long deluge. I prayed for sound airline engineering.

I’ve fished in every quarter of Scotland from uninhabited Hebridean islands, to the northern isles, among the remotest hill lochs of the Shieldaig forest, via the Flow Country and through Knoydart to the borders and Galloway. I’ve fished on the edge of the Arctic Sea in the most northern areas of Finland and Norway.

But I have never, ever, felt so far from civilisation as I felt in the midst of the Canadian tundra. Beyond the sinister uranium mines, beyond the last Indian settlements into the virgin homeland of the wolf and the black bear, the arctic fox and the moose. Without that 8-seater Piper Chieftan there was simply no way back.

And the fishing? Yes, yes, the fishing. Trolling a home-tied size 0 weighted fly at about 20ft I picked up several 6-8lb lake trout in half an hour. The real monsters lay about 60ft down on the thermocline, and were taken with huge 8in spoons and rigs of about 12in long.

Our Cree guide shook his head with dismay at my sea-trout rod and feathered concoctions. The big fish were already retreating to the depths in preparation for the nine-month winter and none of my tackle would reach down to tempt them. Still, it seemed to me quite likely that fly-fishing rod records would soon be broken on these northern lakes.

And amid the rapids of the immense Fond du Lac river we encountered grayling nirvana. In the space of an hour I had more than 12 fish captured and released. On one unforgettable cast I had two 3lb fish attached to two flies and airborne simultaneously.

On our first evening at the lodge there was international camaraderie; the exchange of angling anecdotes is as useful a social lubricant as a couple of large gins. There were groups of friends and workmates from Minnesota, Milwaukee and Florida enjoying the anticipation, the exhilaration, the chill. A mix of white and blue-collar men, mainly.

But there was one interesting couple. He, rugged early 40s, fit and tanned with the cut crystal looks and confidence that suggested he might have appeared in front of a lens regularly somewhere. She, slightly younger, equally fit and with the face and figure to catch any roving eye. They were clearly not married. At least to each other. They fished only twice to our knowledge and sight-seeing wasn’t on offer, but their demeanour indicated that any other pursuits were of an indoor nature.

The didn’t mix with the rest of the guests and my host was being ultra-discreet other than to say they were Canadian.

It was perhaps an unlikely venue for a clandestine few days away with your boss’s secretary or Dolores from the typing pool, but it did have one hugely redeeming feature: Hatchet Lake was the classic get-away-from-it-all location. The chances of bumping into a friend of a friend were low, the passers-by non-existent and the remote-factor was simply off the scale.

On our second evening we sat down to dinner in the main lodge. A large and cheerful woman with a strong Canadian accent came to take our order. She had not been around when we arrived and as I spoke, she interrupted.

“What part of Scotland are you from?” she asked.

“Glasgow”, I said.

“What part?”

When I replied, she volunteered in a drawl: “No kidding, that’s where I’m from; my sister still lives there”.

Not only did her sister indeed still live in our neighbourhood, but my wife had been having coffee with the woman in question and some acquaintances only the week before.

It was one of those strange “small world” moments. I’d travelled halfway around the world to one of the most desolate regions in north America to write an angling travelogue only to find that the family of the woman who headed up all the domestic services at this isolated fishing resort lived more or less next door to me in Glasgow.

It has to be said that we ate and dined in some style until our departure by which time word of my encounter had already arrived back home in Scotland.

I thought before I left, I might confide this bizarre coincidence to the Canadian couple with the permanent “Do Not Disturb” notice on their chalet door.

But why spoil their fun; there was little point. If there was any message in this close encounter in the wilds of Canada it was a simple one: the world is a smaller place than it looks, so just remember that sometimes illicit poaching can land you in deeper water than you expect.

2 Responses

[…] Chapter 6 – Getting Away From It All « Between The Lines bxttlines.wordpress.com/2009/10/02/chapter-6-%E2%80%93-getting-away-from-it-all – view page – cached SOMETIMES IT is necessary to do things back to front and start with the end of a story. This one finishes in the early autumn frosts of northern Canada, amongst the stunted pines and endless… (Read more)SOMETIMES IT is necessary to do things back to front and start with the end of a story. This one finishes in the early autumn frosts of northern Canada, amongst the stunted pines and endless impenetrable wilderness of the sub-Arctic tundra with the howl of the timber wolf providing a haunting sound track to the nightly kaleidoscope of Aurora Borealis. (Read less) — From the page […]

[…] » Blog …Related Blogs on blue troutRIO Trout LT (Light Touch) Fly Line « Blue Quill Angler BlogChapter 6 – Getting Away From It All « Between The Lines Duration: 00:02:51 Rating: View: 105From: feyspriteKeywords: […]